We have seen the hot air balloons ascend and descend, and now it’s time to visit Albuquerque and the surrounding area.

Albuquerque is smack-dab in the middle of the desert, within the northern, upper edges of the Chihuahuan Desert ecoregion. The average annual precipitation is less than half of evaporation, and it has an average of 3,415 sunshine hours per year.

Okay, it’s not quite like this photograph. But it is arid and hot.

The Desert

We are always surprised that grass and trees can grow in a place with so much sun and so little rain. Notice the barb-wire fence which helps keep wildlife off the road.

The desert is in an old, vast river valley where water washed away the softer rock, over millions of years, and left behind plateaus of harder rock. Wherever you see concentrations of green plants is a sign that there is slightly more water than in the surrounding area.

Over the flat desert pass long trains. These freight trains can be over a mile in length. The only restriction, in most US states, is that they can not block a crossing for more than 20 minutes. We can’t tell how long this one is, but it’s long. Long.

We step out of the car. There are no sounds. In all directions is the beauty of the desert, uncompromised but for the single ribbon of highway.

We find this amusing. In our US culture, we are told to refer to American Indians as “Native Americans”, for reasons. Yet, Native Americans refer to themselves as Indians. And they live in an Indian village.

We need to watch less TV and spend more time in the real world, I think.

We stop at a rest stop and take a photograph of the small town across the highway. It has a Mediterranean feel to it, an air of simplicity and healthy living, of community. If looks to us like a place that is part of the desert, by design, because the inhabitants are, indeed, part of the desert.

Sandstone Bluffs and a Natural Arch

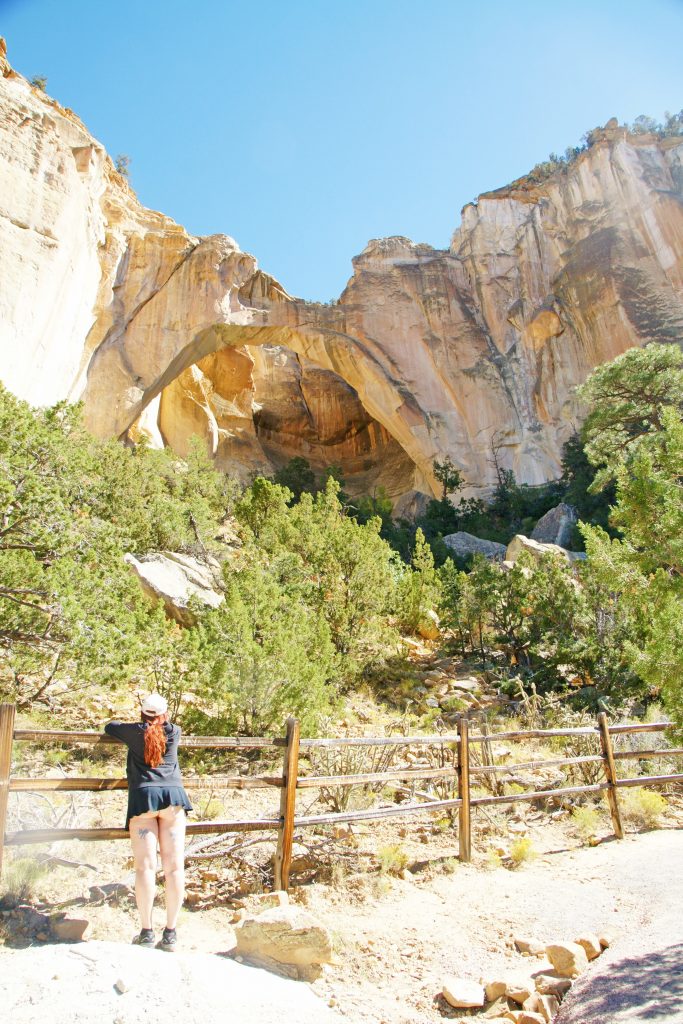

We drive without a destination and come to a small parking lot on a mesa, with a trail leading into the hills. A sign tells us there is a sandstone arch a short hike away.

To our surprise, the mesa is covered with an abundance of dark green conifer trees. Notice, too, the lichen on the orange rock.

The black rock in the distance is probably basalt.

It is difficult to tell from this photograph (and we are not allowed to get very close), but if you could pass under the archway, you would be in an enclosed rock formation. The shortest part of the arch looks like it might fall at any time, which geologically means within the next million years or so.

You can see the sunlight on the other side of the arch. The coloring on the rock wall gives the illusion that the rock has been twisted to form the arch.

The path is circular and we follow a different route back to our car. The lone tree trunk is interesting. In wetter parts of the world, a dead tree would quickly be absorbed by animals and plants, its parts reused. In the desert, such a thing takes a much longer time. We are impressed there are so few dead trees and bushes. These are very hardy plants.

Kasha-Katuwe Tent Rocks National Monument

We drive to Kasha-Katuwe Tent Rocks National Monument, north of Albuquerque.

Kasha-Katuwe is located on the Pajarito Plateau between 5700 and 6400 feet (1737–1951 m) above sea level. The area owes its geology to layers of volcanic rock and ash deposited by pyroclastic flow from eruptions within the volcanic field of the Jemez Mountains that occurred 6 to 7 million years ago. Weathering and erosion of these layers created slot canyons and tent rocks. The tent rocks are composed of soft pumice and tuff. Most of the tent rocks have a distinctly conical shape and some retain their caprocks of harder stone. The tent rocks vary in height from a few feet to 90 feet.

We were about to climb the rock when we noticed the sign. Oh, well….

We climb, following the trail that varies from flat to fairly steep. There are tent rocks all along the way.

If you look closely, you can see that there are dozens of tent rocks of all sizes on the side of the mountain, including a double-tent rock.

This little tent rock interests us. It seems out of place, a large (almost) sphere on a narrow neck, with no other tent rocks near it.

We climb higher and find a nest of tent rocks, including another with a spherical head and many with heads looking like they are about to tumble. And we can better see why they are called “tent” rocks.

The path takes us through a deep slot canyon. It’s pretty cool both in concept and in temperature. We pause here for a short time, enjoying the relief from the heat.

We are near the top of the mesa now, and have a wonderful view of the tent rocks and their caps. It’s pretty cool that these structures occur naturally.

Other visitors to the National Monument told us there was a face in the rock, but we didn’t see it until we took a photograph and looked at it on a monitor.

We hiked about 1.5 miles and climbed about 630 feet, and we our final reward is this perfect view of the New Mexico desert. That stripe of green is the result of the Rio Grande, which flows south after exiting the Cochiti Lake, a man-made dammed lake.

Santa Fe National Forest

As we travel north, we come upon the 1.6-million-acre Santa Fe National Forest, which is NOT the desert. This national forest encompasses the headwaters of Pecos, Jemez, and Gallinas Rivers, and is home to turkeys, elk, deer, and bears.

Since it is October, we enjoy the fall colors of the golden aspen. The difference in elevation, with mountains rising from 5,300 feet to 13,100 feet, make a marked difference in ecology from the desert, only a few miles south.

The sign at the lookout point shows in the distance the location of the Ortiz Mountains, Sandia Peak, Albuquerque, Sante Fe, Tetilla Peak, and Pajarito Mountain. Note that a few of these are ski areas in winter.

Paseo del Bosque Trail

Despite what I said earlier, Albuquerque is not in a desert. No one builds a city in a desert. In fact, Albuquerque straddles the Rio Grande and is, in some areas, lush.

The Paseo del Bosque Trail is 16 miles of cottonwood trees and shrubs. In autumn, along the river, the weather is comfortably cool.

Albuquerque Greenery

Where there are rivers and irrigation, there is greenery.

Behind our house is a field that is irrigated and next to that field is a profusion of native plants, including these giant sunflowers, which are not really native to New Mexico.

The cultivated field has a path and we follow it, enjoying the smell of the grass and the soil.

There are many, many grasshoppers here. They are too small for me to get a good photograph illustrating their abundance, but if we walk messily through the native grass, we are bombarded with wayward grasshoppers as they jump in all directions.

It’s warm here, but the air so dry that it is comfortable being outside despite the sun. Gotta be careful, though; those plants have stickers and, if something is going to be stuck in me, I don’t want it to be a plant!

In the morning and evening, when it’s not too hot, it is common for us to see riders on horseback and folks walking their dogs.

Where you have food, you have rodents, and where you have rodents, you have critters like coyotes. In fact, we see coyotes often in these fields.

Due to the presence of water and grain, we frequently see Canada geese. Albuquerque is in their winter nesting range.

Sadly, it’s time to go home. We love being here, experiencing the magnificent hot air balloons, the desert, the mountains, and the whole New Mexico feeling. Someday, I think, we will return.