We continue our adventure in Ciudad de México with a trip to Museo Mural Diego Rivera.

Museo Mural Diego Rivera

Diego María de la Concepción Juan Nepomuceno Estanislao de la Rivera y Barrientos Acosta y Rodríguez was a prominent Mexican painter and two-time husband to noted hirsute-eyebrowed Magdalena Carmen Frida Kahlo y Calderón. The Museo Mural Diego Rivera is a museum in Mexico City where Diego Rivera’s 1946-47 mural Sueño de una Tarde Dominical en la Alameda Central is located, and that’s where we are traveling today.

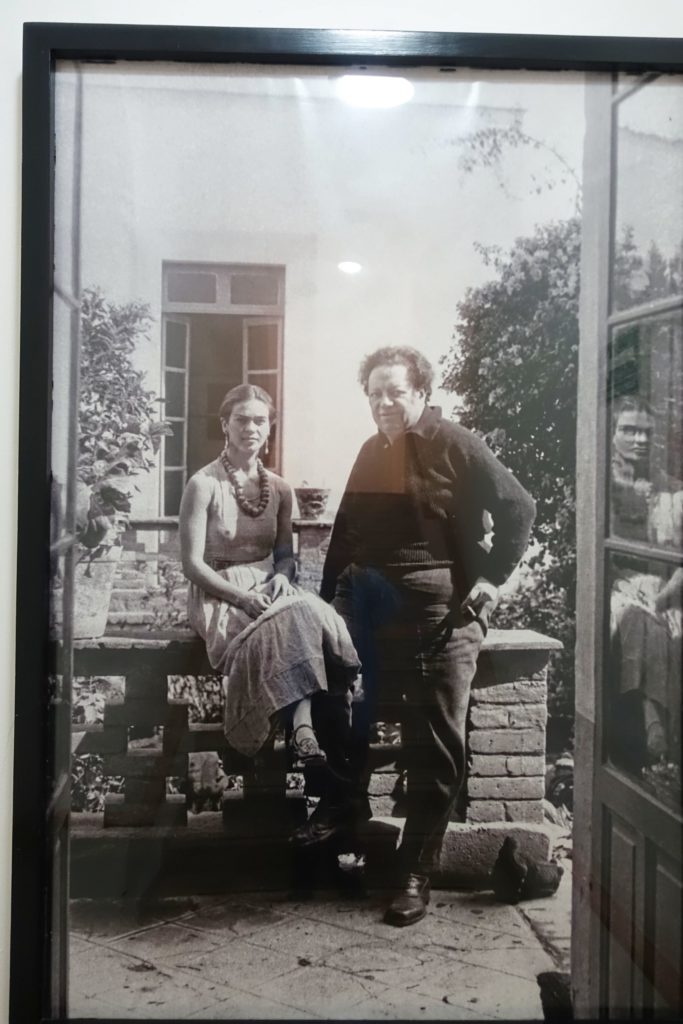

This wonderful photograph of Diego Rivera and Frido Kahlo is displayed in an obscure stairwell in the museum. The two artists look so casual, seemingly unaware of their role in history.

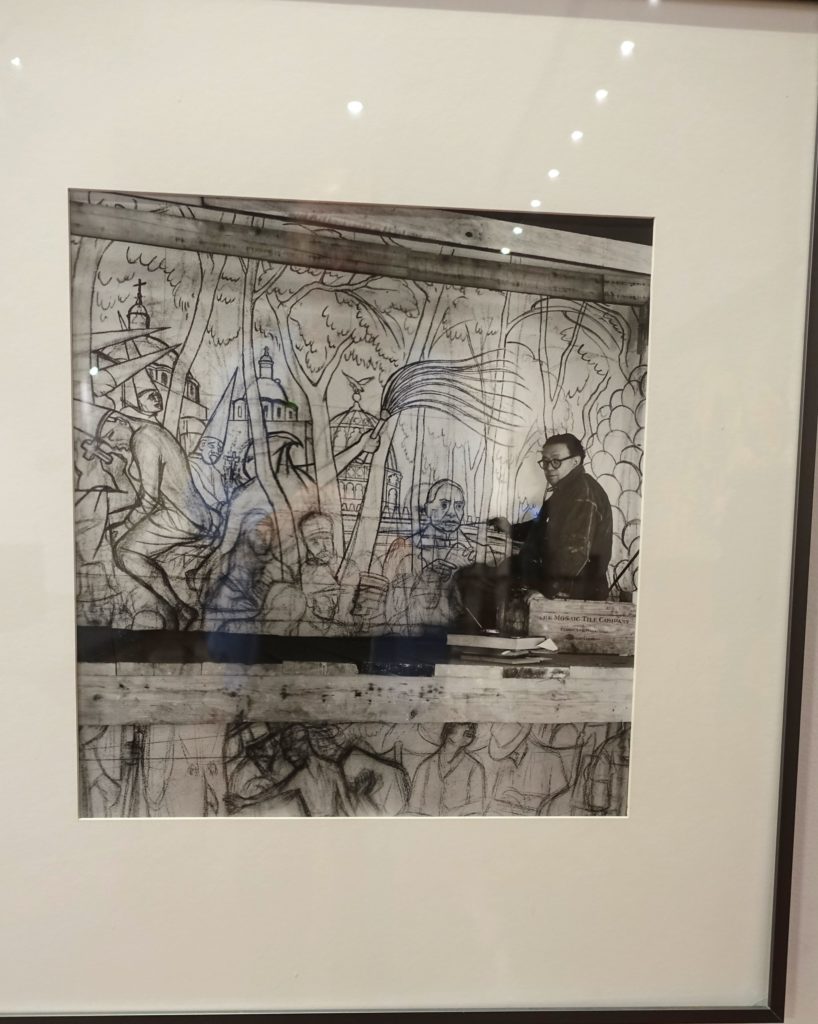

This photograph illustrates the time and effort that such a mural requires. What might appear in the final painting to be a casual after-thought is indeed carefully constructed in precise layers and dimension.

According to the internet: In 1946, architect Carlos Obregón Santacilia asked Diego Rivera to create a mural for the Hotel del Prado’s Versalles dining room. The subject for the mural was the Alameda Central, which was across the street from the hotel. It was finished in 1947. The mural shows more than 150 figures, some of them leading characters the history of Mexico: Hernán Cortés, Benito Juárez, Maximiliano de Habsburgo, Francisco I. Madero, Porfirio Díaz. In addition, individuals from different social classes appear, including street vendors and revolutionaries. It also shows Frida Kahlo and other wives of the artist, as well as some of his daughters; the Alameda Central itself can be seen in the background. The painter said: “[The mural] is composed of memories of my life, my childhood and my youth and goes from 1895 to 1910. All the characters are dreaming, some asleep on benches and others, walking and talking.”

At the museum, there is a guide in Spanish and English explaining most of the characters and activities depicted in the mural. You can read some of it at SmartHistory.org.

A Shopping Mall

There seems to be an unending series of art projects in Mexico City, including those found in shopping malls.

Mexican artists seem comfortable with mixing and matching art styles. The Babylonian king Hammurabi mingles with folks from the Day of the Dead who are posed in a Terrance-and-Phillip-esque posture. Confusing? Yes. Mexican? Of course. 🙂

In this scene, a skeleton is embalming someone, ensuring that they never become a skeleton. Weird, right?

In this scene, Egyptian gods indicate towards a sarcophagus, while in the foreground, an Aztec skeleton stands ready near an open casket.

And finally, we have just a regular reproduction from an Egyptian tomb. Go figure.

More Street Art

As with many objet d’art, there is undoubtedly meaning and purpose, sometimes known only to the originator. For this piece, there are far more coins being dumped from the cornucopia than could have fit in the cornucopia. Magic? Poetic license? And act of god?

This little fellow has a plaque that reads “Jackpot!” and cryptically includes, “Para exposicion permanente en las instalaciones de la loteria nacional edificio “el Moro”. Obra inspirada en los niños gritones como homenaje a esta institucion.” Perhaps “los niños gritones” is some kind of metaphor?

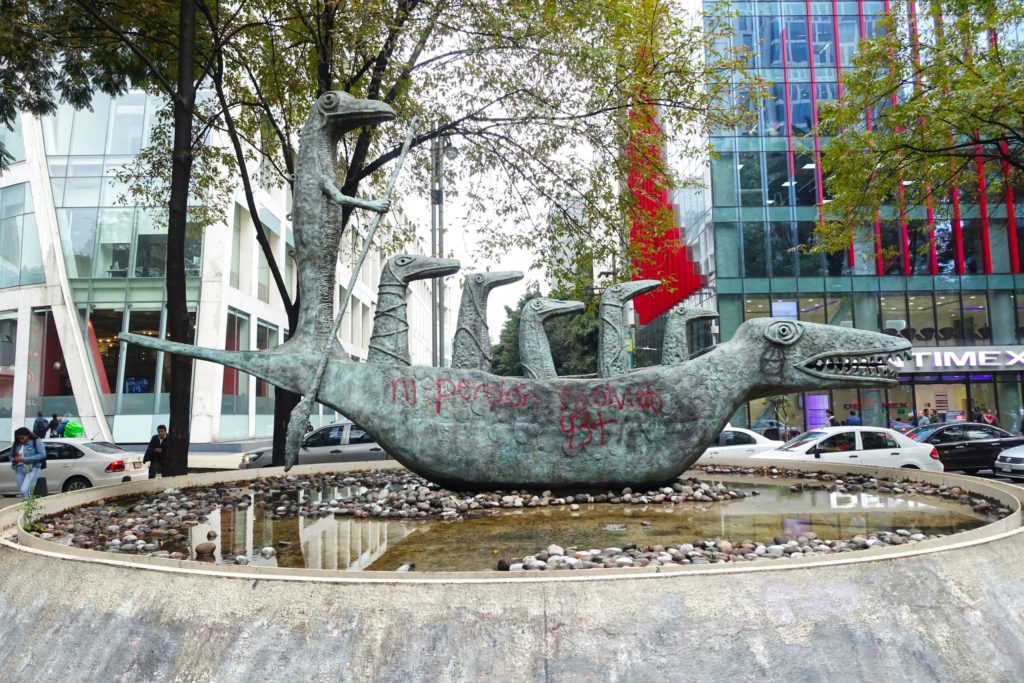

Some lizard people have sliced open another lizard, removed its legs, and are using it as a boat. Also, some of the passengers are entangled in rope. So, there.

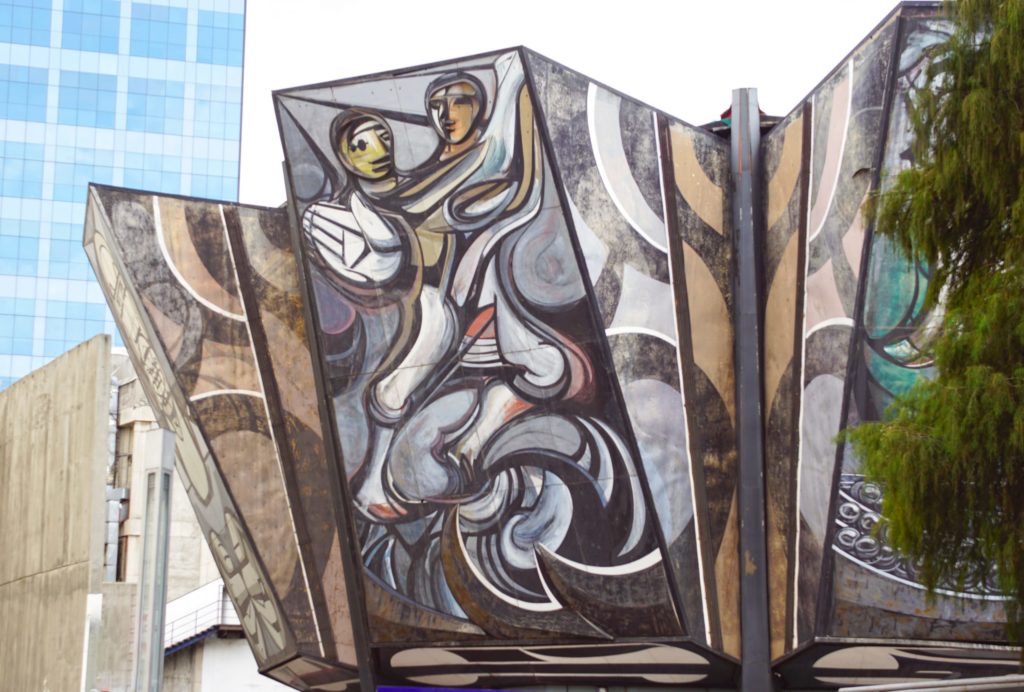

This mural is painted on part of a building that seems to have no purpose but to be available to have murals painted on it. It’s a bit too abstract for me, but I am impressed by the really big robot-like hand.

“Son, clean up this mess!” “What am I supposed to do with it, Dad?” “Son, you can stick it to the wall for all I care.” “Even the sharp metal bits, Dad?” “Sure, why not, kid?”

And, if you look closely, there is a surprised face staring out, as if frozen in carbonite.

A household is not complete without a gaily dressed skeleton (that is worried about rain) decorating the front door.

I know what you are thinking. “Why is the belayer‘s head completely enclosed in a black helmet?”

A large primate with no fingers hopes to make a living in Mexico City paying a banjo. I guess anything is possible if you really believe.

Avenida Paseo de la Reforma

“Mexico City residents take over the center every Sunday morning; cars are banned. The Reforma Avenue is transformed into a huge street circuit with the Ángel de la Independencia as reference. Young and old, groups of friends, students, athletes and families flood the streets to have a workout. Children learn to ride their bikes or skate with their parents. Dogs trot happily with their owners. For a few hours, Reforma is the territory of pedestrians, athletes and citizens.”

Sunday morning on Mexico City’s busiest throughfare.[/caption]

We wake up on Sunday morning to a slightly less-noisy Mexico City and discover that the avenue in front of our hotel/Airbnb is host of people walking, running, biking, and skating.

We put on our walking shoes and join in the fun!

Palacio de Correos de México

Let’s visit La Quinta Casa De Correos Palacio Postal!

The Palacio de Correos de México (Postal Palace of Mexico City) also known as the “Correo Mayor” (Main Post Office) is located in the historic center of Mexico City, on the Eje Central (Lazaro Cardenas) near the Palacio de Bellas Artes. It was built in 1907, when the Post Office here became a separate government entity. Its design and construction was the most modern of the time, including a very eclectic style mixing several different traditions mainly Neo-Plateresque into a very complex design.

The post office has a higher level of security than we expect for a building that just collected letters and packages.

The building has a steel frame and a foundation built on an enormous grid of steel beams, which has allowed it to withstand a number of earthquakes and has avoided the subsidence problem that plagues many buildings in Mexico City.

The marble floors and shelves combine with bronze and iron window frames manufactured in Florence, Italy. The main stairway is characterized by two separate ramps that come together to form a landing. They also seem to cross on the second landing above, after which each move off in their own direction.

We were very concerned about where this was printed, and felt waves of relief wash over us to finally discover the truth.

The main postal area has quite a different feeling to it than most post offices in America, which are little more than processing centers for people. We don’t know what the (perhaps) wooden structure is; at first we thought it was a safe, then realized that, although this building is heavily fortified, it’s not a bank.

The Post Office’s architectural style is highly eclectic, with the building being classed as Art Nouveau, Spanish Renaissance Revival, Plateresque, Spanish Rococo style, Elizabethan Gothic, Elizabethan Plateresque and Venetian Gothic Revival and/or a mixture of each. The building also has Moorish, Neoclassical, Baroque and Art Deco elements.

Please enjoy more photographs of this beautiful building.

Museo Nacional de Antropología

The Museo Nacional de Antropología is the largest and most visited museum in Mexico, and contains significant archaeological and anthropological artifacts from Mexico’s pre-Columbian heritage,

There are a number of exhibits that are standard in archaeological and anthropological museums, but it’s the Aztec artifacts that we are here to see. There are so many displays that Octavio Paz criticized the museum’s making the Mexica (Aztec) hall central, saying the “exaltation and glorification of Mexico-Tenochtitlan transforms the Museum of Anthropology into a temple.”

According to the internet:

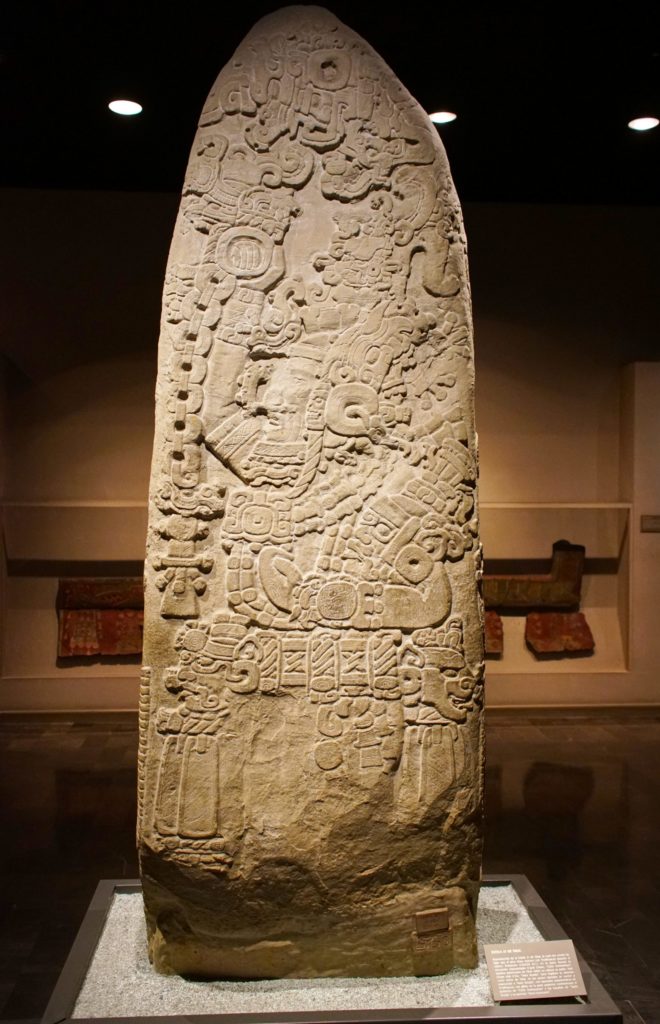

This stele or monolith block is showing us an image of a ruler of the city of Tikal. His name is K’awil Chann, well called the “Stormy Sky.” Above his head is his father, Huh Chaan Mah K’ina, “Curly Nose,” which symbolizes that he makes his right or appointment as Lord of Tikal legitimate.

This wake is important because it is a concrete proof that the Teotihuacan culture exerted influence on the Maya area. There are 700 kilometers of distance between the current Teotihuacan and the Mayan zone, but the Teotihuacans did go to that area and left their influence. For example, the cult of Quetzalcoatl or pottery was bequeathed to the Maya. The main contact was with the cities of Tikal and Copan, leaving a great cultural and commercial influence like cocoa.

Upon turning, this wake also has embedded glyphs that describe scenes that commemorate the government of “Stormy Sky” and the feats of “Curly Nose.” Glyphs are minimal signs of Mayan writing, equivalent to a word or a syllable.

Based on the information on the plaque, this fellow, named Cocijo, is a lightening deity of the Zapotec civilization of southern Mexico. In Zapotec myth, he made the sun, moon, stars, seasons, land, mountains, rivers, plants and animals, and day and night by exhaling and creating everything from his breath.

This statue is an Atlantean figure. According to the internet: These figures are considered to be “massive statues of Toltec warriors”. They take their name from the European tradition of similar Atlas or Atalante figures in classical architecture, which was then revived in the Renaissance and especially popular in Baroque architecture. Atlantean here refers to the figures’ supporting posture, alluding to the load-bearing Titan Atlas, not Atlantis.

This fellow is called “El Creador” Morelos, Xochicalco during the Epiclassic period (AD 700 – 900). According to the internet: Represents an adult kneeling, bearded and with fangs. It has two penises that intermingle with cocoa leaves that rise behind the arms and run down the back to top in the chest with a knot. One of the bats reaches the thigh, while the other reaches the left forearm. Another reading would be that the character is sitting on a cocoa plant. It is linked to the fertility and divine origin of the rulers of Xochicalco.

Mictlantecuhtli was the Aztec god of death and the principle god of the underworld. Throughout Mesoamerican culture, they practiced human sacrifice and ritual cannibalism to placate this god. The worship of Miclantecuhtli was ongoing with the arrival of Europeans in the Americas. Aztec associated owls with death, so Mictlantecuhtli is often depicted wearing owl feathers in his headdress. He is also depicted with a skeletal shape with knives in his headdress to represent the wind of knives which souls encounter on their way to the underworld. Sometimes Mictlantecuhtli may also be depicted as a skeleton covered with blood wearing a necklace of eyeballs or wearing clothes of paper, a common offering to the dead. Human bones are used as his ear plugs, too.

There were two life-size clay statues of Mictlantecuhtli at the entrances to the House of Eagles at the Great Temple of Tenochtitlan.

This is the head of Quetzalcoatl, the feathered serpent god. It’s not the standard way the god is represented; however, it can be represented as resplendent quetzals, rattlesnakes (coatl meaning “serpent” in Nahuatl), crows, and macaws.

In Aztec mythology, Chicomecōātl (“Seven Serpent”) was the Aztec goddess of agriculture during the Middle Culture period. She is sometimes called “goddess of nourishment”, a goddess of plenty and the female aspect of maize.

La Serpiente de Cascabel is to be left to its own affairs in any age.

Xōchipilli is the god of art, games, beauty, dance, flowers, and song in Aztec mythology. His name contains the Nahuatl words xōchitl (“flower”) and pilli (either “prince” or “child”), and hence means “flower prince”. Xōchipilli has also been interpreted as the patron of both homosexuals and male prostitutes.

Among the important rituals that were practiced in general in Mesoamerica, and particularly in Tenochtitlan, there was the human sacrifice. The belief in the constant renewal of the vital force of the gods from the blood and hearts of the captives of war, made this ritual would increase. This magnificent piece, made of andesite, was found under the courtyard of the Marques del Apartado building in the corner of Argentina and Donceles in the Historical Center of Mexico City. Together with its partner, a cuauhxicalli (container for offerings) in the shape of an eagle, they are representations of complementary opposite elements. The cuauhxicalli had several shapes, but all served to store the hearts and blood of the captives sacrificed, as well as other type of offerings to the gods. In the back of the animal there is a decorated bowl with two pictures, one of the God Huitzilopochtli and another of the God Tezcatlipoca, both with pierced earlobes.

Chacmool (also spelled chac-mool) is the term used to refer to a particular form of pre-Columbian Mesoamerican sculpture depicting a reclining figure with its head facing 90 degrees from the front, supporting itself on its elbows and supporting a bowl or a disk upon its stomach. These figures possibly symbolized slain warriors carrying offerings to the gods; the bowl upon the chest was used to hold sacrificial offerings, including pulque, tamales, tortillas, tobacco, turkeys, feathers and incense. In an Aztec example, the receptacle is a cuauhxicalli (a stone bowl to receive sacrificed human hearts).

The Aztec sun stone is a late post-classic Mexica sculpture. The stone is 358 centimeters in diameter and 98 centimeters thick, and weighs 24,590 kg. The sculpted motifs that cover the surface of the stone refer to central components of the Mexica cosmogony. The state-sponsored monument linked aspects of Aztec ideology such as the importance of violence and warfare, the cosmic cycles, and the nature of the relationship between gods and man. The Aztec elite used this relationship with the cosmos and the bloodshed often associated with it to maintain control over the population, and the Sun Stone was a tool in which the ideology was visually manifested.

According to the plaque next to this sculpture: The one sculpture which identified the Mexicas above all others is the Stone of the Sun. Because of its symbolic content, with the names of the days and the cosmogonic suns, it was incorrectly identified as the Aztec Calendar.

This is a large gladiatorial sacrificial altar, known as a temalacatl, which was not finished because of a deep crack that runs from one side to the center of the piece at the rear. Despite the fracture, it must have been used to stage the fights between warriors in the tlacaxipehualiztli ceremony.

In the design of the disk, the face of Xiuhtecuhtli – emerging from the earth hole, holding a pair of human hearts and showing his tongue transformed in a sacrificial knife – can be recognized.; his is surrounded by the four suns that preceded the Fifth Sun, in turn inscribed in the sequence of the 20 say signs, framed with the figure of the Sun with its four beams symmetrically accompanied by sacrificial sharp points. The star is surrounded by two Xiuhcoatl or “Fire serpents”, which carry it across the heavens.

Displayed is a replica of the headdress worn by Moctezuma II (also spelled Montezuma, Moteuczoma, Motecuhzoma, Motēuczōmah, Muteczuma, and referred to in full by early Nahuatl texts as Motecuhzoma Xocoyotzin (Moctezuma the Younger). Moctezuma II was the ninth tlatoani or ruler of Tenochtitlán, reigning from 1502 to 1520. The first contact between indigenous civilizations of Mesoamerica and Europeans took place during his reign, and he was killed during the initial stages of the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire, when conquistador Hernán Cortés and his men fought to take over the Aztec capital Tenochtitlan.

However, we don’t know anything about this hat.

The Mayan Ball Game, although having a non-awesome name, had its share of excitement. For example, in Aztec rules, “The Aztec game drew passionate support from huge crowds, often accompanied by large-scale betting. People lost their food, clothes, and even sold their children and themselves into slavery on the outcome of the game. The Spanish eventually banned it, not simply because of the large crowds it attracted but because it was more than just a game. For the ball court was a place of sacrifice, an arena where the head of the losers would be impaled on a skull rack besides the court and their blood was offered as food for the gods.” However, in the Mayan version, “In ritual games, the leader of the losing team would be sacrificed, and his skull would then be used as the core around which a new rubber ball would be made.” Sweet.

The Olmec people built colossal heads, conveniently called Olmec colossal heads. All portray mature individuals with fleshy cheeks, flat noses, and slightly crossed eyes; their physical characteristics correspond to a type that is still common among the inhabitants of Tabasco and Veracruz. The backs of the monuments often are flat. The boulders were brought from the Sierra de los Tuxtlas mountains of Veracruz. Given that the extremely large slabs of stone used in their production were transported over large distances (over 150 kilometers (93 mi)), requiring a great deal of human effort and resources, it is thought that the monuments represent portraits of powerful individual Olmec rulers. Each of the known examples has a distinctive headdress. The heads were variously arranged in lines or groups at major Olmec centers, but the method and logistics used to transport the stone to these sites remain unclear.

The museum has thoughtfully constructed Mesoamerican ruins so we can pretend we are explorers making important discoveries!

This is a reproduction of the sculpture of Mictlāntēcutli in El Zapotal. Mictlāntēuctli, meaning “Lord of Mictlān”), in Aztec mythology, was a god of the dead and the king of Mictlān, the lowest and northernmost section of the underworld. He was one of the principal gods of the Aztecs and was the most prominent of several gods and goddesses of death and the underworld. The worship of Mictlantecuhtli sometimes involved ritual cannibalism, with human flesh being consumed in and around the temple.

This replica shows the facade of Sak Xok Nah in Ek’ Balam, Yucatán. In the real temple was buried Ukit Kan Leʼk Tokʼ, called El Trono (‘The Throne’).

This is a replica of Hochob (Mayan for “place of the corn stalks”). The buildings’ facades which symbolize the open mouths of serpents, in reference to the Earth monster. Large and small stone blocks that are perfectly placed form emotional masks of the god Itzamná, who’s menacing open jaws highlight the entrance of buildings which almost certainly housed temples, chambers, and priestly chambers.

According to a plaque near the building: Hochob is located in the Chenes region and means “place of ears.” It is well known as during the nineteenth century the peasants of the region used the ruins as a barn. The set of monumental architecture is distributed on a hill overlooking the broad and fertile valley. Although the settlement was occupied throughout the Classic period, it was during the Late and Late Classic when it reached its splendor and was abandoned around 1100 AD. C. It has been suggested that the development of mask covers began in the Rio Bec region during the Late Classic, whose most complete expression was reflected in the Chenes region. Building 2 is best known for the zoomorphic mask of its facade, which constitutes a distinctive feature of the “Chanes style”. It is a representation of the monster of the earth or Itzamnaah with the jaws open, bordered by waterfalls of masks in profile. At both ends we observe the silhouette of a house with a palm roof, whose access shows the fabric of a mat as a symbol of royal authority. The bodies of two snakes are intertwined on the mask, while the façade is topped by an openwork crest with 13 anthropomorphic sculptures.

Despite this being a museum of anthropology, one of the most distinctive features is the umbrella waterfall in the main courtyard. As with other water-esque features here in Mexico City, it is a bit too cold for us to indulge. 😐

Museo de Chocolate

There are museums in Mexico City that are not dedicated to macabre people and events.

Located in a 1909 house in Colonia Juarez, in the street of Milan Esquina Roma, MUCHO opens its doors to an elegant and cozy atmosphere around chocolate and cocoa.

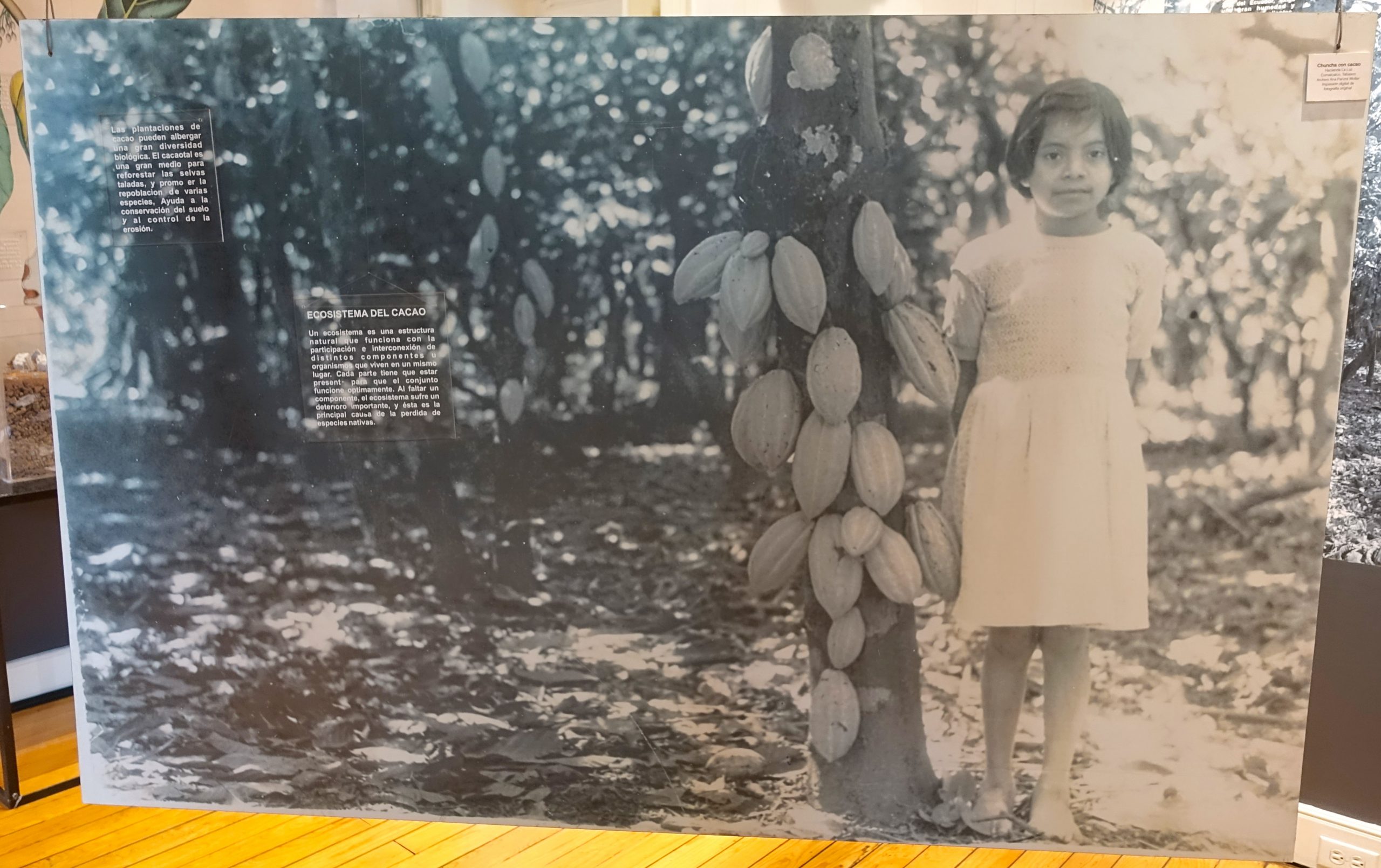

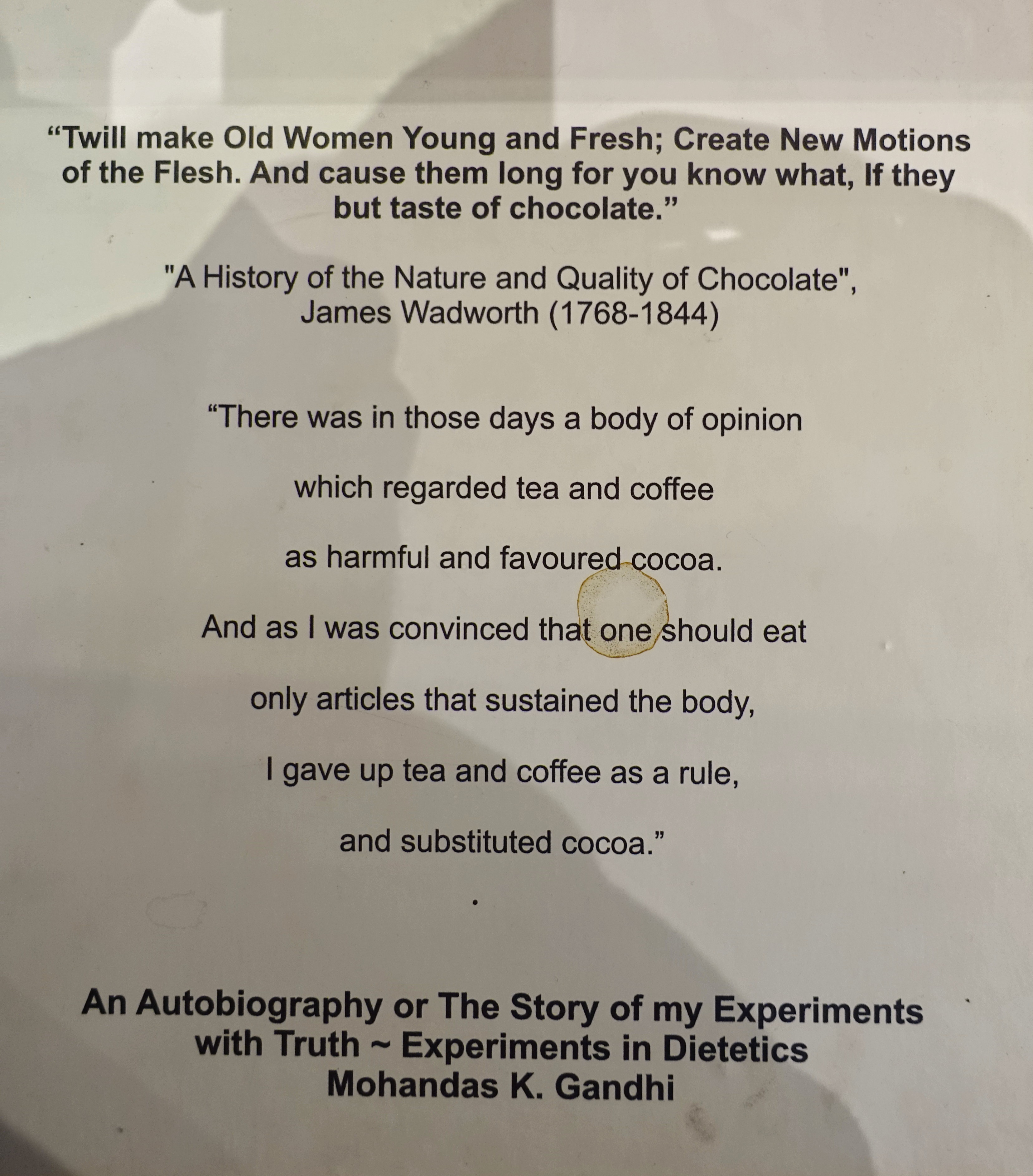

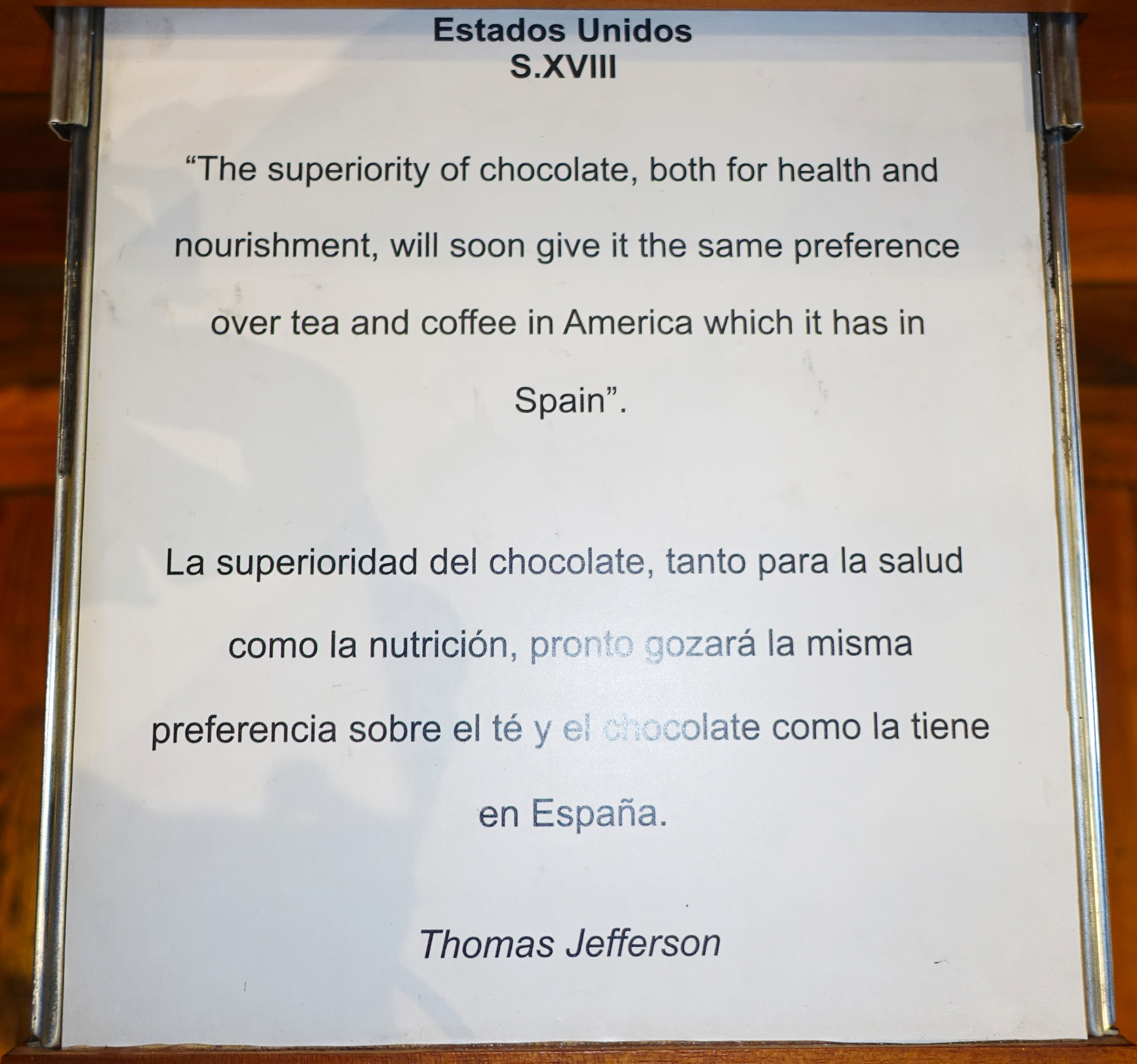

The Chocolate Museum is more than just eating chocolate. It is also a place of learning and understanding.

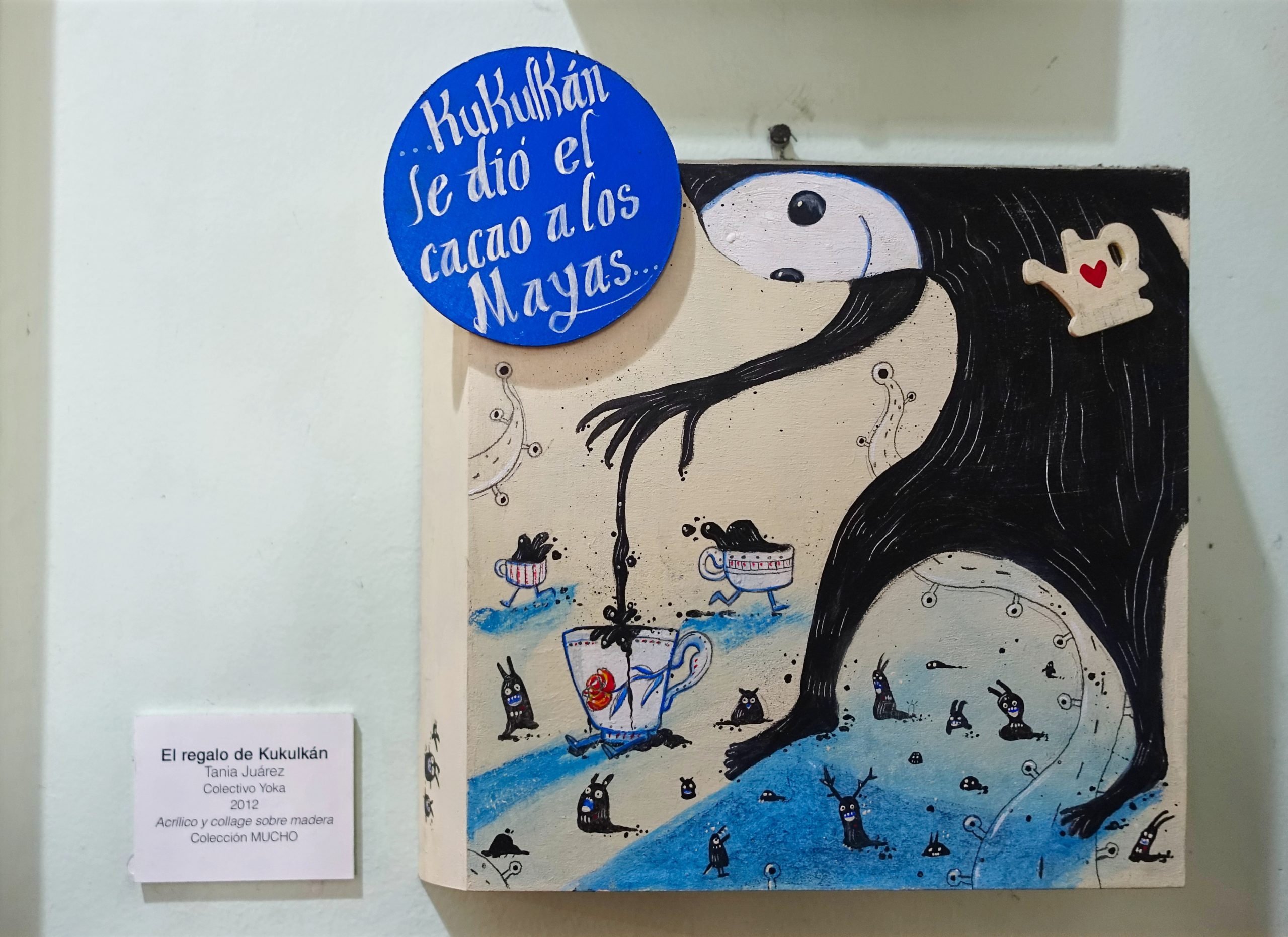

Cultivation, use, and cultural elaboration of cacao were early and extensive in Mesoamerica. Ceramic vessels with residues from the preparation of cacao beverages have been found at archaeological sites dating back to the Early Formative (1900–900 BC) period. For example, one such vessel found at an Olmec archaeological site on the Gulf Coast of Veracruz, Mexico dates cacao’s preparation by pre-Olmec peoples as early as 1750 BC. On the Pacific coast of Chiapas, Mexico, a Mokaya archaeological site provides evidence of cacao beverages dating even earlier, to 1900 BC. The initial domestication was probably related to the making of a fermented, thus alcoholic, beverage. In 2018, researchers who analyzed the genome of cultivated cacao trees concluded that the domesticated cacao trees all originated from a single domestication event that occurred about 3,600 years ago somewhere in Central America.

Chocolate has been marketed as liquids, solids, and foamy creams. All are delicious.

In Europe, high-society embraced chocolate, adding sugar as necessary and apparently in equal amounts.

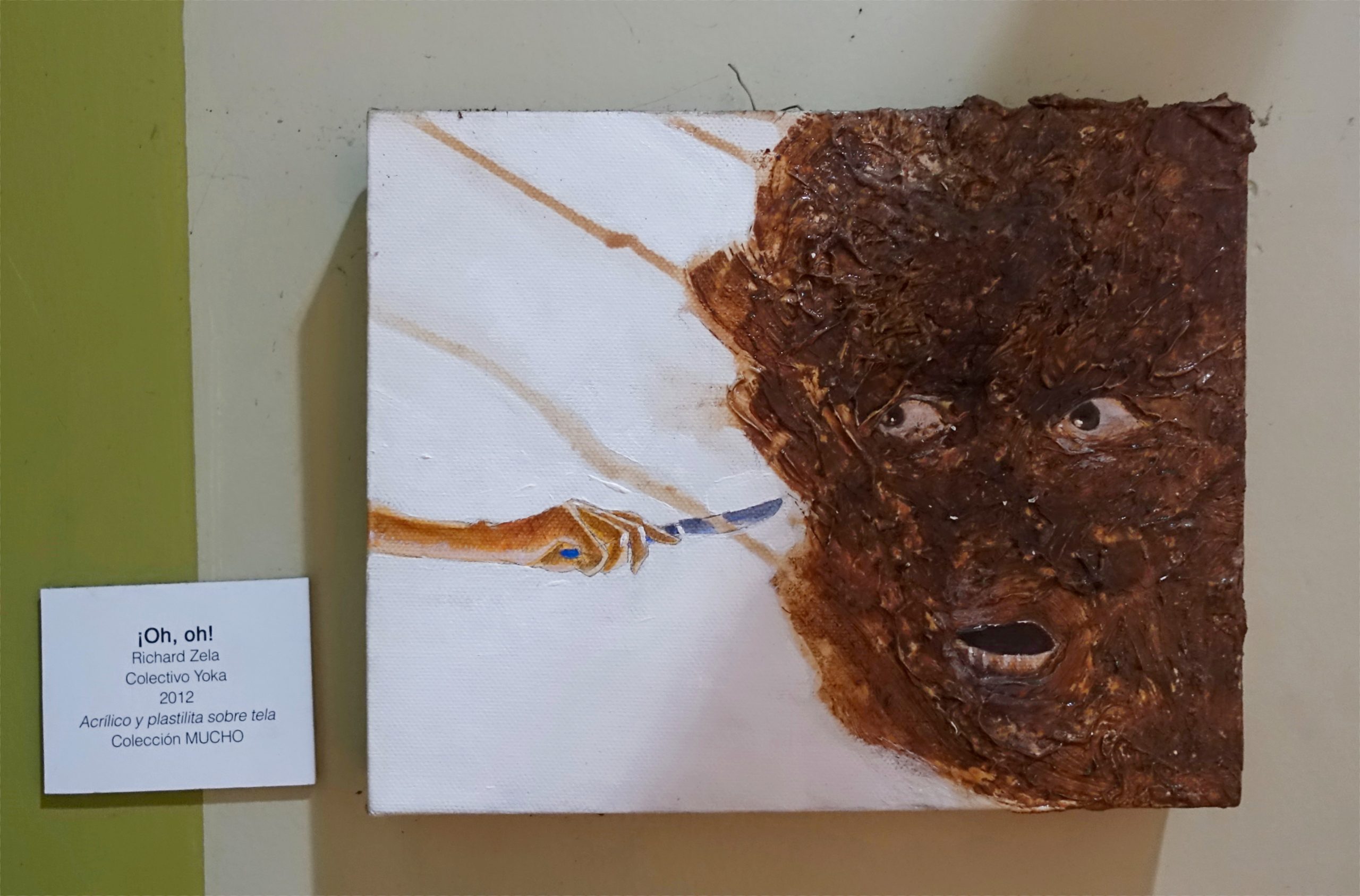

We are lectured, “Don’t play with your food.” Fortunately, not everyone takes such scoldings to heart.

Beauty is in the eye of the beholder; Behold this chocolate-inspired creations.

Nothing says “yummy” like displaying the insects found in and around chocolate.

Apparently, ticks are chocolatey, because they are just one of the many insects whose image is etched in the wooden floor.

I think his cheeks are filled with chocolate. At least he’s photogenic, right?

It’s no surprise that spiders are found in tropical forests, but do we really need a close-up? Apparently, we do.

There are many fun objet d’art in this room, but the smell of chocolate leads us to this drum of powdered goodness. We’re not really sure what it’s for, but it smells really, really good.

It turns out the chocolate powder is but a few inches deep, so we do use it as a vehicle to make our own works of art.

There is a small room covered with these cookie-like objects affixed to the wall. They are waxy and smell very chocolatey. And, since it’s food, we are allowed to take a selfie. 😎

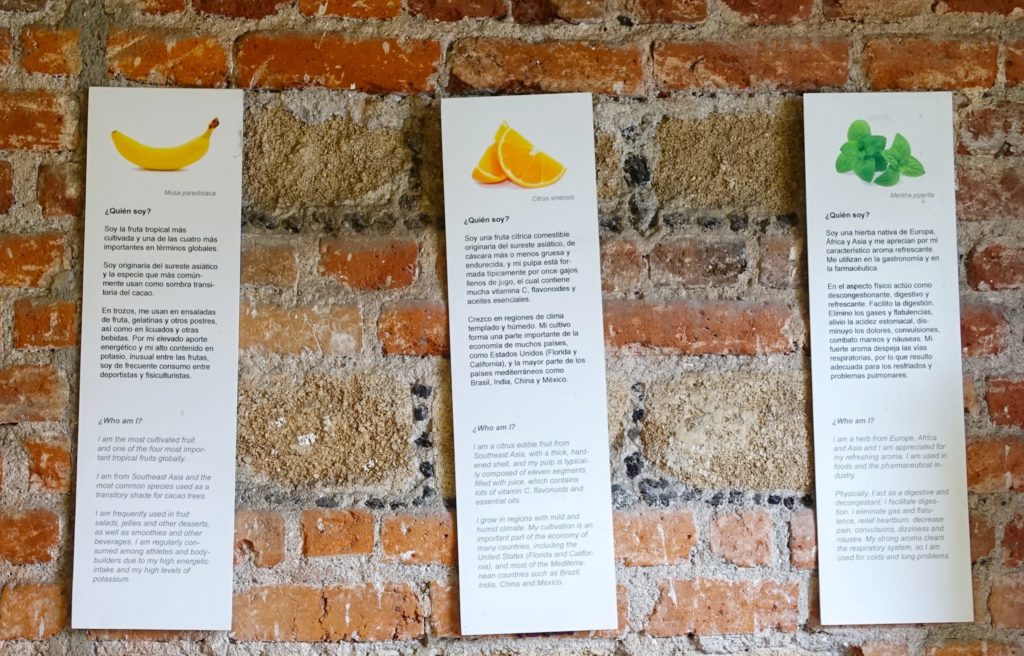

But, of course, there is more to delicious confectionaries and libations than just chocolate; we mix many flavorful plants with chocolate to derive even more delicious goodness.

So how does this work?

There are vials of liquid with small bulbs to squeeze. Hover your nose over the opening and try to figure out the scent.

It is more difficult than you’d think, in part because the room smells strongly of chocolate, so they whiff of fragrance is always flavored with chocolate. However, we don’t mind. 😀

And if you really like chocolate, you’ll love the chocolate-themed furniture. Sadly, none of it is edible.

However, other chocolate is quite edible, and in enough colors and styles to make famed chocolatier Willy Wonka happy.

I’m sure that the Aztec people would have appreciated chocolate shaped like the top of a skull. Yum!

And for those who enjoy more standardized chocolate—oh, wait. I see some skull faces in there. Never mind.

Feature here are chocolate turtles shaped like the famous reptile.

Tragically, we avoid the addictive lumps of sugary delight and instead enjoy a cup of smooth chocolate warmth.

At the other end of the cafe, a woman works on her laptop while holding a folder full of paper while talking on her phone, a small container of food resting on the table, under a glamorous La Calavera Catrina surrounded by leaves and flower petals.

Ah, Mexico City, you are a charmer.